A deeply ingrained and enduring symbol for Bethel College derives from a piece of farm machinery obsolete almost before it touched Kansas soil.

Proud Threshers, from left to right: sophomore Brendan Bergen, senior Aaron Rudeen, sophomore Leland Brown, freshman Hannah Brinker

and senior Chris Riesen.

Proud Threshers, from left to right: sophomore Brendan Bergen, senior Aaron Rudeen, sophomore Leland Brown, freshman Hannah Brinker

and senior Chris Riesen.I’m proud to be an old piece of farm equipment!

declared the Spring Fling 2011 T-shirt (yellow) designed by Audra Miller ’14. The concept was so well received, it was reprised this year in a new design (maroon).

Why would Bethel College adopt as its symbol a farming implement that was obsolete before it ever appeared on the soil of the American frontier from which the institution sprang – a lump of limestone more likely to have crumbled away into a pile of pebbles or become a birdbath, a schoolyard ornament or a flagpole base than to have actually separated wheat from chaff? What are the useful metaphors to be found there?

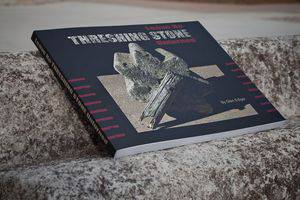

Bethel’s four threshing stones and threshing stones in general have been getting a lot of attention lately – due in part to Bethel’s 125th anniversary year, and the curiosity of Bethel alumnus Glen Ediger ’75, North Newton, that sparked his research into the threshing stone in North America.

Glen Ediger ’75, pictured here with the Ad Building threshing stone, notes that telling the stone’s story requires consideration of

Glen Ediger ’75, pictured here with the Ad Building threshing stone, notes that telling the stone’s story requires consideration of international politics, the opening of the Wild West, the railroad, the search for religious freedom,plus archaeology, evolution, changes in world food supplies and farming technology, and ancient to modern history. Much like a liberal arts education.

In the same way currents of history joined to result in Glen curating an exhibit, Threshing Stone: Mennonite Artifact & Icon,

currently at Kauffman Museum, as well as producing his first book, Leave No Threshing Stone Unturned, in time for the quasquicentennial celebrations, so did a number of currents coalesce to produce a symbol for Bethel College that goes well beyond the Mennonite.

The threshing stone’s provenance is, however, most certainly Mennonite. John Thiesen ’82, Bethel co-director of libraries, noted in a 2007 Faculty Seminar talk on the threshing stone as symbol that Bethel’s particular seven-toothed stone is a uniquely Mennonite artifact.

Even more specific, it is unique to Ukrainian Mennonites from the 19th-century Russian Empire. Neither John nor Glen, in his later study, has found a single Bethel-type

threshing stone now in existence that does not have some tie to that group.

Threshing stone as farm machinery

The initial wave of Mennonite migration to Kansas and the Great Plains began around 1874, consisting largely of those who had been living in the Ukraine and had developed a thriving economy based on farming in a region well-suited to growing wheat.

The technology these immigrant Mennonites knew was 800- to 900-pound threshing stones that horses pulled over the spread stalks of wheat. The stones knocked the wheat kernels from the stalks, which could then be raked off, leaving the kernels to be gathered and further processed.

As Glen points out in Leave No Threshing Stone Unturned, however, it did not take American farm implement dealers very long to realize there was a potential client base newly arrived in Kansas with cash in their pockets. Mennonites brought wooden threshing stone patterns in their trunks from the Ukraine and, as best Glen’s research has uncovered, had between 100 and 200 of them made from the native Kansas limestone being quarried then (and to this day) in Marion and Chase counties. Some were used for one or two harvest seasons. Others were never used at all. Within five years of the initial Mennonite migration to Kansas, farmers were using threshing machines to harvest their grain.

These were the Mennonites who would found Bethel College in 1887 and from whom the money would eventually be raised to build the Administration Building. Had they come to the United States only a little later, there would likely have been little or no reason to associate the threshing stone with Bethel.

Threshing stone embraced as symbol

In spring 1903, according to the Bethel College Monthly from June of that year, Cornelius H. Wedel, Bethel’s first president, set a threshing stone up in his yard, located about where the Fine Arts Center is now. The stone came from the Goessel-area farm of Heinrich Richert, Wedel’s father-in-law.

That was the threshing stone’s first appearance in any kind of Bethel record. It didn’t show up again until late 1934, when it was adopted as Bethel’s official symbol. John says there is no clear source for this decision – he assumes it came from then-President Edmund G. Kaufman ’16, who held office from 1932-52. There was a brief ceremony held Nov. 16, 1934, in which two threshing stones (one of them the one from C.H. Wedel’s yard) were placed in front of Science Hall, now the James A. Will Family Academic Center.

Nevertheless, the Bethel sports mascot remained the Graymaroon, rather unimaginatively named for the college’s colors. Then, in 1959, the Bethel board appointed J. Winfield Fretz, who had taught sociology at Bethel since 1942, interim president. Looking for new administrative ideas and a fresh vision, in spring 1960, Fretz secured the services of a consultant from the national liberal arts colleges’ organization, who was the first to offer the threshing stone to Bethel as a concrete symbol,

John says.

Bethel has a distinctive symbol which could be used to typify [its] values, and make them relevant not only to its own heritage and constituency, but to the larger Kansas community and the world.

– Thomas E. Jones, consultant, 1960

Just days after Jones’ visit, Fretz gave a chapel talk in which – apparently unaware that it had been declared Bethel’s official symbol 26 years earlier – he argued for the college adopting the threshing stone as its athletic mascot. Among other things, Fretz said, the threshing stone stands for something significant [and] suggests a process – something dynamic

and also suggests the ideals of industry … a symbol of motion, power, firmness.

Threshing stone in the 21st century

Jump ahead 40 years, to 2001-02 when there was a major revision of Bethel’s graphic standards, including implementation of what is now called the legacy symbol, created by Ken Hiebert ’53 Gwynedd, Pa., and still the base for any official use of the threshing stone as a design element. Since 1960 and especially since the beginning of the 21st century, Bethel has seen a wide variety of creative and mostly sanctioned uses made of the threshing stone and the Bethel Thresher

that include but go well beyond its role as sports mascot.

About three years ago, Glen Ediger – artist, product designer, inventor, collector, athletic booster and historian – and his wife, Karen (Unruh) Ediger ’76, inherited a broken threshing stone from her family farm near Goessel.

Glen wanted to know more about this object. When he began digging, he quickly made some surprising discoveries. Aside from John Thiesen’s 2007 research on the threshing stone as Bethel symbol, no one else had ever made a serious study of them. Rather than the thousands of threshing stones scattered across the Great Plains that he expected to find, there was solid evidence of just more than 100, almost all found within a four-county area in south central Kansas.

In the introduction to Leave No Threshing Stone Unturned, Glen writes that his quest to find all the threshing stones there are

resulted in a narrative that is far more than a boring story about rocks, but one that traces a fascinating journey which crosses the paths from many directions at a specific time in history.

Both Bethel’s Ad Building and a threshing stone are made of limestone formed from millions of years of sedimentation and compression – material that comes out of the Kansas soil. The Mennonites who dreamed and built Bethel may not go back that many years but can still cite centuries of history that brought them to the piece of ground where they built the first Mennonite college of its kind in the world.

Whether or not the Bethel threshing stones ever actually touched grain, they were built to be 800-pound objects pulled by one or more 1,000-pound horses that could nonetheless perform the delicate task of shaking grains of wheat from their stalks, beautifully illustrating the biblical metaphor of separating the wheat from the chaff.

In the same way, perhaps, a liberal arts education challenges students to carefully think about what they believe and why, and to discern from that a career, a calling or the next step on the journey.

A Student is a Seed

Just as this threshing stone helped the Mennonite pioneers free life-giving kernels of wheat from their dry outer husks, so Bethel College commits itself to help students discover their own goodness, that they might grow in intellect, character and spirit, becoming their best selves.– epigraph for the threshing stone that stands in front of the Ad Building, written by Nathan Bartel ’02, assistant professor of literary studies

Bethel students today may be more comfortable with and even more knowledgeable about the Thresher than were the students of yesteryear. A bookend tradition that started in 2006-07 has first-time freshmen and transfer students touching a threshing stone as they leave their first convocation in the fall to start the Walk of Welcome around the Green.

Interested in exploring some more?

Visit the special exhibit, Threshing Stone: Mennonite Artifact & Icon,

at Kauffman Museum in North Newton,

on display through Jan. 20, 2013.

Attend Kauffman Museum’s Sunday-Afternoon-at-the-Museum program Jan. 6, 2013 for a special presentation: What’s a Thresher? Bethel College’s Symbolic History

by John Thiesen ’82, archivist at the Mennonite Library and Archives. Free to the public; www.bethelks.edu/kauffman.

Leave No Threshing Stone Unturned is available for purchase at the Kauffman Museum gift shop. Call 316-283-1612.