The bell came to Bethel in 1956. But if Bethel supporters had had their way, there would have been a bell from the beginning.

The original plans from the firm Varney Brothers for the Administration Building, writes Keith Sprunger in Bethel College of Kansas 1887-2012, called for an elaborate four-story structure with an awe-inspiring tower with a bell.

Those plans motivated a group of Newton women to form the Bethel Bell Club for the purpose of raising money to buy a bell.1

The Varney plans, though, were too elaborate and definitely too expensive for German Mennonite tastes. The second architect firm, Proudfoot & Bird, scaled back considerably, eliminating the tower and bell. (The disappointed Bethel Bell Club members nevertheless decided to turn their fund-raising efforts to buying a large American flag to fly over the building, which it did at the dedication in 1893.)

Out on the prairies of western Kansas, a bell hung in the Antelope Schoolhouse in Thomas County, from the time that area was settled [early 1900s] until 1940,

according to Levi Goossen ’59, writing in response to an inquiry from Archivist John Thiesen ’82 in 1995.

The school closed in 1940. Goossen’s father, Frank D. Goossen, bought the bell at the Antelope auction and gave it to the congregation of Meadow Mennonite Church, Mingo, to hang in their church tower.

It was used many times during my growing up years,Levi writes.

He believes the bell hung in the church until 1952, when the congregation built a new building and decided not to re-hang the bell. Franz purchased it again at auction and brought it to the Goossen farmstead, 3 miles east and 2 miles south of Mingo,

where it was rung only occasionally just for the fun of it,

Levi writes.

In 1956, Frank decided to give the bell to Kauffman Museum. He took it there during fall homecoming weekend that year.

And there it sat quietly for the next 13 years.

Ringing for peace

During that time, the campus climates changed, at Bethel and across the country. The 1960s brought a growing movement for civil rights for African Americans as well as deepening opposition to the war in Vietnam.

In 1967, Sprunger says in Bethel College of Kansas, Calvin Trillin, then a writer for the New Yorker, came to Kansas to check out the antiwar movement in the Great Plains. Trillin reported that the Bethel Peace Club was a hot spot of antiwar activity,

whose 20-30 members were the kind of young Mennonites who believe that social and peace concerns must be demonstrated

and that the war in Vietnam [is] particularly immoral.

Before this era, Peace Club activity had consisted mostly of informational discussions and occasional trips to Intercollegiate Peace Fellowship gatherings, but as the war heated up, the Peace Club, aided by sympathetic faculty, moved into action.

2

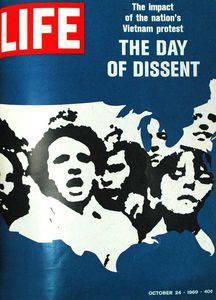

The Peace Club’s big event

of 1969 was to join the national moratorium movement

against the war. The club’s first meeting in September of that year including brainstorming ideas for how Bethel could participate in a month of activities between mid-October and mid-November. Apparently, Jim Juhnke ’62, a history faculty member, suggested using Bethel’s bell to toll for the dead,

a traditional use for church bells.

Oct. 15, Bethel classes were canceled for the day. There were a number of activities, including convocation at 9:50 a.m. Starting at 10:30, the bell, hauled from its resting place in the museum, was rung every four seconds for 12 hours. This was repeated the next three days, through Oct. 18. The ringing was to commemorate the 38,000-plus U.S. soldiers who had died thus far in Vietnam.

We gave [the ringers] mantras to chant, to measure out the time necessary to wait between rings, so everything was timed right for four days of ringing,

says Kirsten Zerger ’73, one of the event organizers (hers was The power of Love is a part of peace

). She told Sprunger: What made it so powerful and compelling

was incessant ringing for 12 hours a day, for four days straight, making its message – the terrible cost of the war – impossible to ignore.

The Bethel bell proved to be a big attention getter,

Sprunger wrote. [In addition to Life,] NBC, CBS and ABC came to the campus to cover the story … A second Moratorium rally occurred in November in Washington, D.C. The Peace Club was there with its [sic] bell. Bob Mayer [’73, Kansas coordinator for the National Moratorium Day] remembers the trip,

3several car loads of students and faculty … with the bell on a trailer.

Bethel had a place of honor at the big candlelight vigil on the Mall, with the bell ringing in honor of each soldier killed in Vietnam.

Once we had everything set for the ringing,

Kirsten says, it was Bob Mayer who had contacts with the National Moratorium office in D.C., and he let them know what we were planning to do. The national office put that info out to their media contacts, and the rest is history. That’s why we showed up on all three network news programs the night of Oct. 15. We were a great middle-America story.

At the November Moratorium Day in Washington, she remembers that the bell was placed near Arlington National Cemetery, where every demonstrator rang it just before they crossed the bridge to head for the walk in front of the White House.

And with that, the bell became a part of Bethel campus life. It would never go back permanently to its museum resting place.

Ringing for celebration

Beginning in the early to mid-1970s, the bell began seeing more frequent use that wasn’t political in nature.

Harold Schultz, Bethel president 1971-91, started the ongoing practice of ringing in the new school year with the bell at the first convocation.

I considered the bell had a unique story and a unique identity with Bethel’s students … . So let’s make it part of our experience as a Bethel community with the opening of each new year rather than have it merely as a museum artifact unseen and unknown to most students or viewed only as a part of past history (Vietnam); rather, activate it as an excellent symbol/image for ringing in a new school year.

I can’t spot the exact year,

he adds, since I don’t keep a diary, but it was in the mid-’70s (1973-77), I am quite sure.

It may have been 1974, since Phil Fuller ’81 had two stories about the bell in The Bethel Collegian that fall. In the first, The Bethel Bell Appeals to People,

Sept. 19, 1974, Phil wrote that the bell was now the central symbol of the college.

When he asked Jim Juhnke what the bell meant, Jim answered that, to him, it signified death, since in his hometown (Lehigh), a bell tolled whenever someone died.

Phil went on: The bell has become a part of Bethel College history. Professor Juhnke does not believe it to be surprising or too hard to accept if the bell were still a symbol of Bethel College one hundred years from now.

In 1975, Bethel’s football team was well on the way to its first-ever conference title when an ineligible player came to light, meaning all wins to that point were forfeited. The bell was rung then to honor the football team.

And football was at the root of The Collegian’s top news story of 1984-85, the bell controversy.

This time, the Threshers did win the conference championship, their first in 70 years of football at Bethel.

The crucial game was Oct. 27 against Southwestern College. Pumped-up students and faculty (in particular a man still known as one of Bethel’s number-one fans, especially for football, Loren Reusser ’59, then teaching accounting at Bethel) made Oct. 26’s convocation into a pep rally, at which they rang the bell.

They moved it out in front of the Ad Building and then, according to Loren, whenever the bell would ring again during the rest of that day, everyone would rush out to cheer for the Threshers some more.

It was carried by pickup to Winfield the next day, where Bethel beat the Moundbuilders 26-21.

But many students were unhappy with this use of the bell. They felt that using the bell in this manner was inappropriate, in view of the bell’s symbolic status in the past,

Paul Schrag ’86, associate editor, wrote in The Collegian (Nov. 13, 1984).

There was precedent for ringing the bell to honor football. What most riled people, apparently, was indiscriminate ringing

in front of the Ad Building and removing it from campus without permission. (President Schultz was not on campus at the time of the Southwestern game so Dean Marion Deckert ’56 approved its use, not realizing that meant taking it to Winfield.)

Schultz acknowledged to The Collegian that the bell should be used with discretion – if it is used too commonly, it loses some of its mystique.

However,

he added, I do not want the bell to be seen as something so somber that it can only have a very heavy agenda. It should also be allowed to be used on celebrative occasions, within reason.

Carmen Troyer (Fish) ’85, in a letter to the editor on Dec. 12, 1984, wrote: Because the bell belongs to the Bethel community, it should be used for all significant events. … the bell tolls for Bethel. And in that sense, the bell tolls for our number one football team.

Collegian editor-in-chief Mark Siebert ’85 agreed: If athletics are not an important enough part of the school to be honored with the ringing of the bell, they should be discontinued

(Nov. 13, 1984).

Ringing for commemoration

These days, use of the bell has swung back toward sparing – just at the beginning and end of the school year.

When Dale Schrag ’69 was given charge of convocation planning in 2003, he kept the bell-ringing in the opening, but moved the bell to the plaza outside the Fine Arts Center.

Schultz had typically rung it only twice to open school – the bell’s tone is too loud for more than that inside Memorial Hall or, nowadays, Krehbiel Auditorium. That tradition carried on until Dale took over planning.

I felt the bell needed to be rung more than twice or not at all,

he says. The president of the college and the president of Student Senate, ears protected with cotton, start ringing the bell at 10:55 a.m., leading to convo at 11.

And when commencement moved outdoors to newly completed Thresher Stadium in 2008, Dale began also ringing the bell to signal that the graduates were now processing around the Green, headed for the stadium. When bad weather forced commencement back into Mem Hall this year, Dale stood out in the rain and rang the bell just the same.

Though the bell is living a quieter life again these days, it seems Jim Juhnke’s words nearly 40 years ago about it being a Bethel symbol 100 years from now

will prove true.

Mark Siebert wrote in 1984:

[The bell’s] power lies in the hearts and minds of the people on campus. The act of ringing the bell should unite the campus …, all our joys and sorrows.