A major facet of Bethel College’s celebration of its 125 years has been welcoming publication of a new book-length history of the college.

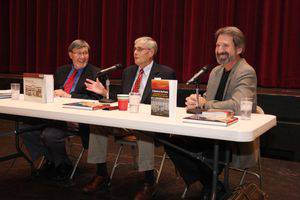

Keith L. Sprunger, Oswald H. Wedel Professor Emeritus of History, and author of the book, Bethel College of Kansas, 1887-2012, also gave the 2012 Menno Simons Lectures at Bethel.

Keith L. Sprunger, Oswald H. Wedel Professor Emeritus of History, and author of the book, Bethel College of Kansas, 1887-2012, also gave the 2012 Menno Simons Lectures at Bethel.Keith L. Sprunger, Oswald H. Wedel Professor Emeritus of History, and author of the book, Bethel College of Kansas, 1887-2012, also gave the 2012 Menno Simons Lectures at Bethel.

By tradition, the second of the four-lecture series occurs during Monday convocation, making it the one with by far the largest audience of current students.

As such, Sprunger chose to treat student voices,

heard through postcards and underground newspapers and, to a lesser extent, yearbooks and T-shirts.

I wanted to discover what students were doing and thinking when they weren’t in the classroom,

he said.

Photo postcards showed things like student dress and campus buildings from the time, while the messages give a grassroots view of ordinary history,

Sprunger said.

As for newspapers, Sprunger said, I found a great deal of valuable material in The Collegian, but there are always faculty sponsors keeping an eye on the student newspaper. So if you wanted to express opinions on the edge, you had to do an underground newspaper that was often slipped under doors.

There hasn’t been an underground paper at Bethel since 2003’s Bethel Collision – on a collision course with authority

– Sprunger said. Today, student opinion is most likely to appear via Facebook or Twitter.

Although Bethel has a long tradition of student nonconformity, going back into the ’40s,

Sprunger said, perhaps the most vocal – and negative – underground voice was The Fly, published irregularly between 1968-70. Its often angry tone reflected the radical changes that occurred on campus in what Sprunger called, in his third lecture, the crucial decade

of the 1960s.

The decade started for Bethel rather quietly and conventionally,

Sprunger said, with an outside consultant doing a study in preparation for a fund drive. He saw a conventional curriculum; a mostly Mennonite, mostly Bethel graduate faculty; wholesome, constructive and Christian

student life – an average Midwestern liberal arts college.

Sprunger noted, The consultant wrote: ‘I covet a little greater measure of excitement.’ Good news – the ’60s [were] on the way.

In Sprunger’s assessment, 1967 was the time when Bethel seemed to have reached a turning point, not only because of national events [e.g., the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War and student activism nationally] but because of Peace Club activities and the growth of more extreme or radical ideas coming to campus and being accepted by students.

The Fly represented the pinnacle of student dissent,

Sprunger said. It had a sharp message: that students must oppose fascism at the national level, illustrated by President Nixon, and at the campus level, represented by President [Orville] Voth ’48. He was hardworking and had a deep love of Bethel but students did not take to him easily. They considered his crew-cut hairstyle unforgivable.

By the end of the decade, Bethel was considerably changed. President Voth resigned. Curriculum changes piled up. No longer a sheltered Kansas Mennonite enclave, Bethel had gone modern and joined the academic and social revolutions.

The consequences, however, were more serious than many knew at the time. Demonstrations on campus (this was the era of Bethel’s 15 minutes of fame

when the non-stop bell-ringing for deaths in Vietnam made Life magazine) and student radicalism in general strained relationships with the Newton community and Bethel's Mennonite constituency.

Former Bethel President D.C. Wedel, who had come back to work in the development office, warned of a dire situation with the relationship with Western District Conference, about half of whose member churches had dropped or reduced support of Bethel over anti-war protests and activities,

Sprunger said.

It had been so bad, in fact, that Sprunger discovered, in his research for the book, the existence of a secret Committee to Close the College.

In 1970, Western District Conference called a special meeting at Bethel at which, despite everything, church representatives voted to assume Bethel’s debt and give the college another chance. The next chapter would be the 20-year presidency of Harold Schultz, 1971-91, and what some would call a Bethel renaissance,

Sprunger said.

That 1970 meeting was crucial. I had gone into it thinking I would need to look for a new position. After that, I felt there was a future for Bethel.

Sprunger said, I started with this idea: In telling the history of Bethel College, I would assume that [almost] everyone did the best they could for Bethel, Even if I saw difficulties or flaws, not to leave it only at that.

Melanie Zuercher